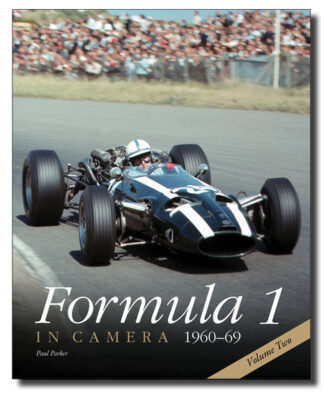

Description

‘We have been great admirers of Parker’s previous histories and have reproduced extracts in Octane before now. This is arguably his best effort yet. You know what to expect: a decade’s worth of Formula 1 imagery with extended – and well-researched – accompanying captions. And the images really are hugely evocative. …

‘There are so many wonderful images here, it’s all too hard not to sound gushing. Countless books are churned out along these lines, but some cost considerably more and a great many have meaningless captions. This is a superb effort and great value. Recommended.’

Octane, BOOK OF THE MONTH

‘Parker’s excellent series continues with a second look at GP racing in the ’60s. … The standard is set early, with a fabulous picture of the Ferrari mechanics pushing a pair of 246 Dinos along the Monaco waterfront, and continues with shots taken at familiar circuits but from different locations. The ’64 Belgian GP, for instance, includes a great photo taken from the Masta Kink, with spectators on the verges, plus trees and lamp-posts nearby. Reproduction is excellent, and the captions full of information.’

Classic & Sports Car

‘It’s a chronological trip through the decade, with splashes of fact-rich text and captions as supporting acts to some wonderful images … a cocktail of beauty, opposite lock, humanity and accessibility. … Marvellous, in a word.

Motor Sport

Paul Parker returns with the next instalment of the superb In Camera series

The acclaimed In Camera series is a stunning photographic tour of the legendary teams, cars, drivers and circuits of Formula 1 and sports-car racing of yesteryear with explanatory comments and analysis, featuring Fangio, Moss, Hawthorn, Clark, Gurney, Hill, Brabham, Stewart, Rindt, Fittipaldi, Hunt, Lauda, Andretti and many more.

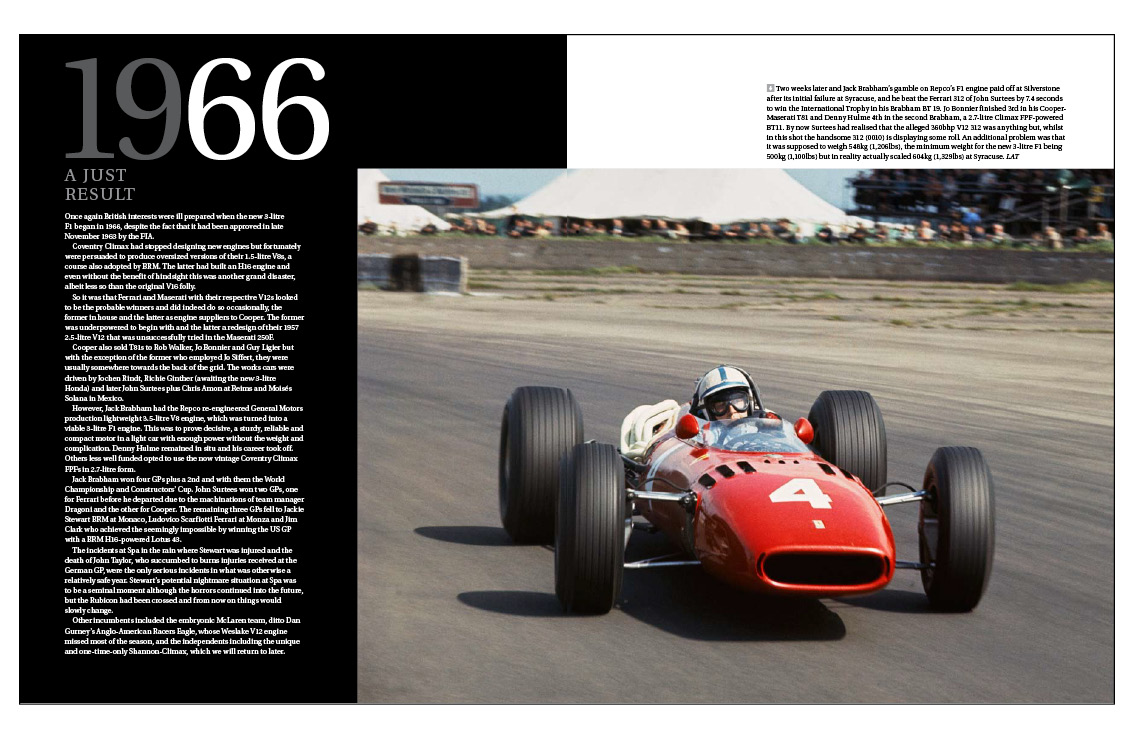

This latest release, Formula 1 in Camera 1960–69 Volume Two, is a second look at surely the most exciting, perilous and ever varied period in Formula 1, from the end of the 2.5-litre/750cc supercharged era (1954–1960), via the small, delicate and sometimes beautiful 1.5-litre machines of 1961–65 to the 3-litre racers in 1966.

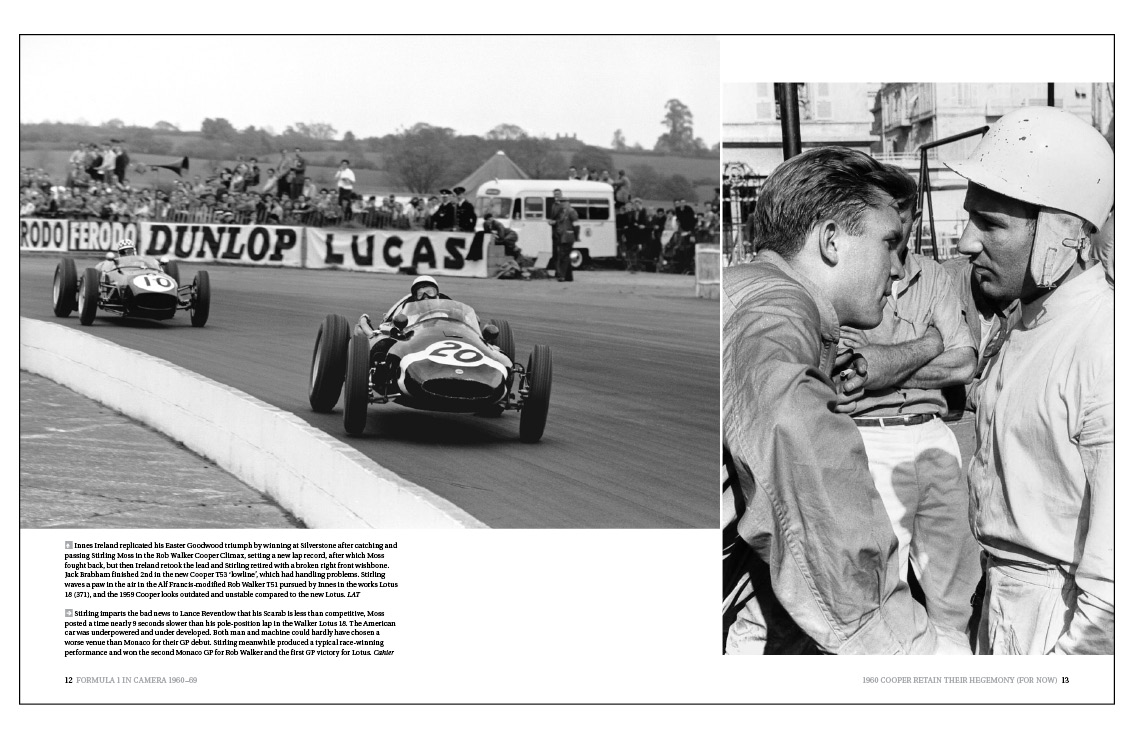

It began with the ongoing supremacy of British cars via John Cooper’s Coventry Climax-powered T51 and T53, Colin Chapman’s answer, the Lotus 18, BRM’s rather belt-and-braces P48 based upon the front-engined P25 and a trio of instantly obsolete front-engined devices and one hanger-on from the late 1950s.

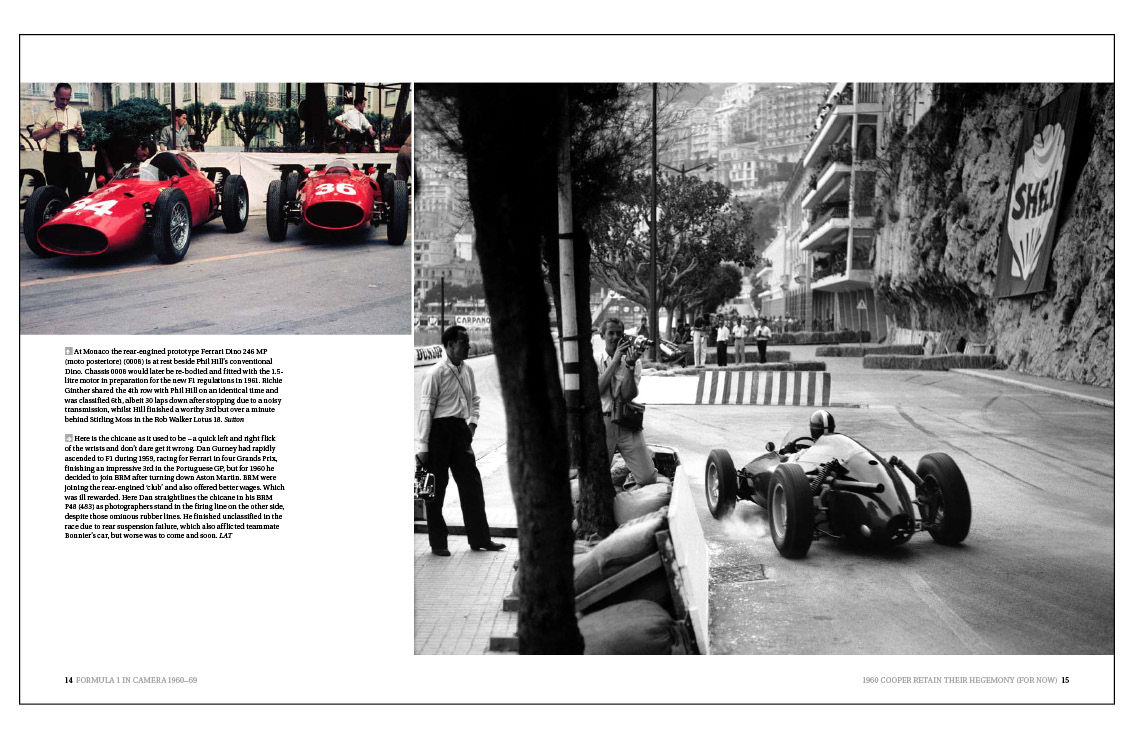

These were the Ferrari Dino 246 (although they would soon join the back-to-front club), Aston Martin’s carried-over DBR4/250, (its successor the DBR5 soon disappeared), Lance Reventlow’s brave but ill-advised Scarab, which had fundamental engine problems but was dynamically superior to its equivalent Italian and British counterparts, and the lowered made-over Vanwall that was slower than it had been years before. There was to be one final front-engined Formula 1 contender, the Ferguson P99, but this only contested one championship GP, in 1961 where it retired, although Moss drove it to victory at Oulton Park that year and it later had considerable success as a hill-climb car.

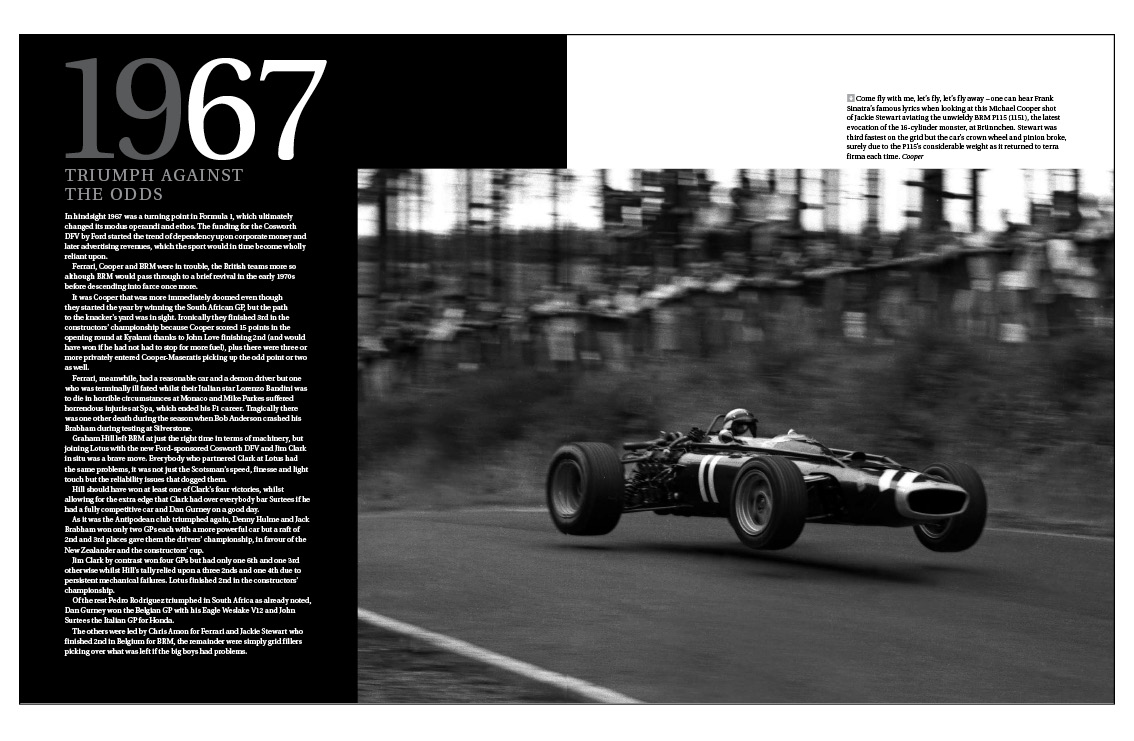

From 1964 onwards, tyres literally broadened their horizons, brakes became serious rather than mere ‘stoppers’ as the cornering speeds rose, with a concomitant increase in straight-line velocity between corners, and inevitably post 1967 ‘wings’ and trim tabs et al sprouted and sought to keep the monsters on the road as the G-forces escalated and braking distances shrank.

Despite the exponential growth in performance the cars nevertheless continued to be fragile, temporary structures that were still, in most instances, potential death traps. Despite this the ethos that had carried motor sport through the worst of times during the 1950s and early 1960s remained intact, but ultimately something had to be done about the perils and somebody had to step forward to address it.

It is questionable how many racers owe their lives to Jackie Stewart’s courageous, but at the time much reviled, stance, but owe them they do. His 1966 Spa accident and the potential but happily unfulfilled consequences of it were a key factor in the future of the sport and ultimately the saved lives of future generations of drivers and spectators. Even so, tragedy was not always avoided and in America fatalities continued to dog track racing.

For latter-day aficionados, however, the very presence of trackside hazards, buildings, telegraph poles, trees, assorted pieces of scenery and not a barrier in sight is one of the undeniable aesthetic attractions of this and earlier eras. Here are not just the obvious suspects like Spa Francorchamps or the Nürburgring but also the narrow roads of Rouen les Essarts and even the grass verge and bank surrounds of Brands Hatch, where spectators were only a few yards from the action.

Today the survivors of this long-ago time are now sadly few, but here we can see them in their pomp together with their contemporaries whose motto seems to have been: ‘we’re here so we are going to race regardless.’

About the author

Paul Parker is the author of Formula 1 in Camera, 1950–59, Formula 1 in Camera, 1960–69 (Volumes One and Two) and Formula 1 in Camera, 1970–79 (Volumes One and Two), along with sister titles covering sports car racing in the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s. Additionally he has written Sixties Motor Racing with Michael Cooper, Jaguar at Le Mans 1950–95, Races, Faces, Places and Klemantaski: Master Motorsports Photographer. He is a freelance writer and a superb photo researcher, with work published in Octane, Motor Sport, Classic Cars, Forza!, Jaguar World Monthly and The Daily Telegraph. He also track tests historic cars and has raced a Lister Jaguar.